What are our days for?

Days, Meaning-Making, and the Small Extraordinary

Days What are days for? Days are where we live. They come, they wake us Time and time over. They are to be happy in: Where can we live but days?Ah, solving that question Brings the priest and the doctor In their long coats Running over the fields.~ Philip Larkin

I’m drawn to Philip Larkin’s poetry for its lucid, conversational language and its pithy honesty about ordinary life. He treats seemingly small, everyday moments as worthy of serious attention, because they are, in fact, important. These are the stock experiences that comprise our existence. His poems confront time, disappointment, and mortality without piety or sentimentality and, if I’m honest, convey a certain cynicism that matches my own temperament. Despite that, there is a secular tenderness that aligns with my own humanist, existential preoccupations.

Larkin’s “Days” came to mind when I recently asked a workshop group: How do you make your life meaningful? It’s a huge question. It can feel like the kind of question best left to experts and authorities—the “priest and the doctor” racing in with answers. No wonder many of us hesitate to look too closely.

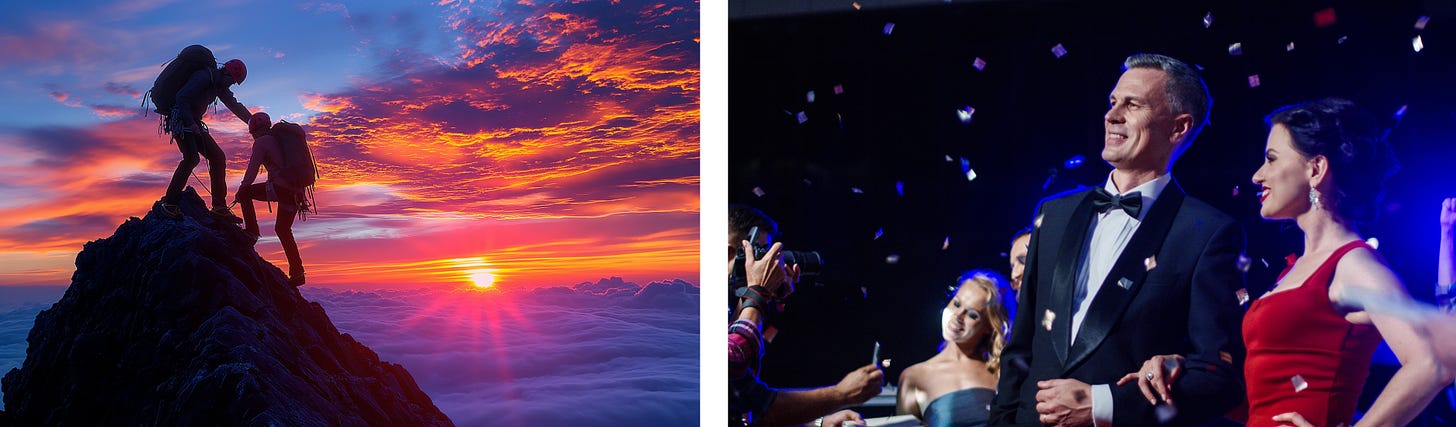

Reflecting on how we bring meaning to our life also may open the door to a sense of failure. We worry that we haven’t done enough, or been enough. That our achievements have fallen far short of our aspirations. That we are not competent to fill those moments of dissatisfaction, frustration, and malaise with wonder, acclaim, and success.

The humanist Algernon D. Black spoke of our “spiritual nature” as an expression of “deep hungers of the human spirit.” One of our mistakes, I think, is imagining that answering “What is the point of my life?” requires a single grand revelation or series of momentous achievements. We ask too much of ourselves at the wrong scale.

In my meaning-making workshops, I invite people to start smaller: to take ordinary experiences in their daily personal and professional lives and make those moments a little more extraordinary. Drawing on concepts of ritual, we explore how to transform a mundane activity into something more intentional, something that asserts simply, this matters.

Habits and routines are useful. They get us through the day. They often run on autopilot: my sleepy-eyed morning shuffle, the commute I barely remember. Rituals, by contrast, are practices carried out with intention and significance. They leave you enlivened.

Rituals give life to our values. They can soothe our anxieties, steady our focus, deepen our sense of belonging, and open us to wonder. They can connect us with one another and with the communities and cultures we inhabit.

But the stakes don’t need to be high. Not everything has to be Ritual, let alone Ritual. On a simple scale from 1 to 10, it’s enough to move some moments from a 2 to a 3. Not every activity needs to be transformed, either. Cleaning my teeth, for example, is not something I personally feel called to ritualize. For illustration, take this more promising moment. One workshop participant realized her morning school drive with her son could become more meaningful, especially with the awareness that an empty nest was not far off. She shaped a simple, intentional pattern of behaviors for those drives, and also recognized the opportunity to invite her son to co-create this fresh practice. The car ride was still practical, but now carried more possibility.

In the workshops, we look at the constituent elements of ritual—intention, symbols, participants, actions, time, place—and use a simple blueprint to design something of our own. In doing so, we see that reviewing how we live needn’t be a painful audit of our inadequacies nor a quest for mystical perfection. With a little attention, we can notice the moments that already matter and gently amplify them.

Another poem that returns to me often: James Wright’s “Lying in a Hammock at William Duffy’s Farm in Pine Island, Minnesota.”

Over my head, I see the bronze butterfly,

Asleep on the black trunk,

Blowing like a leaf in green shadow.

Down the ravine behind the empty house,

The cowbells follow one another

Into the distances of the afternoon.

To my right,

In a field of sunlight between two pines,

The droppings of last year’s horses

Blaze up into golden stones.

I lean back, as the evening darkens and comes on.

A chicken hawk floats over, looking for home.

I have wasted my life.

On my early morning walks around my local park—watching birds in most seasons, stars in winter—I feel the unsettling and joyful recognition of that ambiguous final line: “I have wasted my life.”

Living a meaningful life has always troubled us. We don’t want to squander our finite days. But perhaps the question becomes more livable when we bring it closer to the ground: Where, in my days, can I add a little more intention, connection, or wonder?

What are your days for?

For another poetic eye to attentive living, you might read Rainer Maria Rilke’s “Archaic Torso of Apollo.”